December 1, 2009, will go down in history as the day the Treaty of Lisbon was put into full effect, thus “complet[ing] the process started by the Treaty of Amsterdam [1997] and by the Treaty of Nice [2001] with a view to enhancing the efficiency and democratic legitimacy of the Union and to improving the coherence of its action.” Indeed, this document can even be said to complete a 52-year-old plan first formulated with the European Economic Community established in Rome in 1957.

December 1, 2009, will go down in history as the day the Treaty of Lisbon was put into full effect, thus “complet[ing] the process started by the Treaty of Amsterdam [1997] and by the Treaty of Nice [2001] with a view to enhancing the efficiency and democratic legitimacy of the Union and to improving the coherence of its action.” Indeed, this document can even be said to complete a 52-year-old plan first formulated with the European Economic Community established in Rome in 1957.

The implications and results of the Treaty of Lisbon are certain to be far-reaching, even reaching like Moses Malone into the world of European and international basketball. Ball in Europe takes a look at past, present and future in European Union sports regulation and legislation.

The Past: Bosman, of course, but also Lehtonen

The biggest moment perhaps in all of recent European sport history took place well away from stadiums and in courtrooms, resulting in 1995 in the “Bosman Rule.” And the Bosman Rule went well beyond affecting football across Europe and even pan-European sport; instead Bosman’s case helped redefine European Union provisions regarding free movement of laborers, a key perk for recent EU additions like Poland and Hungary with oodles of white- and blue-collar workers to “export.”

When the Bosman case was decided upon by the EU Court, transfer rules were changed for football clubs across Europe. As the very helpful website EUABC.com summarizes:

Jean-Marc Bosman was a professional football player for the club Liege RC. The club demanded a transfer fee of 11,743,000 BFR (€291,101) for him to change clubs. According to the Court, rules providing a transfer fee after the expiry of the contract are not compatible with the principle of free movement of workers.

In order to promote the development of young players of the home nation some football associations limited to five the number of foreign players each club team was allowed to field. The Court also ruled that limiting the number of professional players who are nationals of other member states is precluded by the Treaty.

(The entire text of the Bosman Rule is available here in 23 languages, but each in a distinct dialect known as “legalese”. You have been warned.)

Though the ruling applied specifically to football, most other professional leagues in various sports across Europe took the Bosman Rule under advisement in reshaping their own bylaws.

The Bosman case was later taken into consideration as a sort of precedent in a 2000 EU Court decision involving FIBA, the Finnish professional league, and the Belgian professional league the FRBSB. The grievance in question involved Team Finland standout Jyri Lehtonen, who played out the 1995-96 season (and his contract) in his home country before attempting to join the FRBSB club Castors Braine to conclude that team’s season.

The EU Court ruling in Jyri Lehtonen and Castors Canada Dry Namur-Braine ASBL v Fédération royale belge des sociétés de basket-ball ASBL (FRBSB) reads, in (small) part, as follows.

12. Mr Lehtonen is a basketball player of Finnish nationality. During the 1995/1996 season he played in a team which took part in the Finnish championship, and after that was over he was engaged by Castors Braine, a club affiliated to the FRBSB, to take part in the final stage of the 1995/1996 Belgian championship. To that end the parties on 3 April 1996 concluded a contract of employment for a remunerated sportsman, under which Mr Lehtonen was to receive BEF 50 000 net per month as fixed remuneration and an additional BEF 15 000 for each match won by the club. … On 5 April 1996 the FRBSB informed Castors Braine that if FIBA did not issue the licence the club might be penalised and that if it fielded Mr Lehtonen it would do so at its own risk.

13. Despite that warning, Castors Braine fielded Mr Lehtonen in the match of 6 April 1996 against Belgacom Quaregnon. The match was won by Castors Braine. On 11 April 1996, following a complaint by Belgacom Quaregnon, the competition department of the FRBSB penalised Castors Braine by awarding to the other club by 20-0 the match in which Mr Lehtonen had taken part in breach of the FIBA rules on transfers of players within the European zone. In the following match, against Pepinster, Castors Braine included Mr Lehtonen on the team sheet but in the end did not field him. The club was again penalised by the award of the match to the other club. As it ran the risk of being penalised again each time it included Mr Lehtonen on the team sheet, or even of being relegated to the lower division in the event of a third default, Castors Braine dispensed with the services of Mr Lehtonen for the playoff matches.

14. On 16 April 1996 Mr Lehtonen and Castors Braine brought proceedings against the FRBSB in the Tribunal de Première Instance, Brussels, sitting to hear applications for interim relief. They sought essentially for the FRBSB to be ordered to lift the penalty imposed on Castors Braine for the match of 6 April 1996 against Belgacom Quaregnon, and to be prohibited from imposing any penalty whatever on the club preventing it from fielding Mr Lehtonen in the 1995/1996 Belgian championship, on pain of a monetary penalty of BEF 100 000 per day of delay in complying with the order.

18. In those circumstances the Tribunal de Première Instance, Brussels … referred the following question to the Court for a preliminary ruling:

Are the rules of a sports federation which prohibit a club from playing a player in the competition for the first time if he has been engaged after a specified date contrary to the Treaty of Rome (in particular Articles 6, 48, 85 and 86) in the case of a professional player who is a national of a Member State of the European Union, notwithstanding the sporting reasons put forward by the federations to justify those rules, namely the need to prevent distortion of the competitions?

Though it seemed to be going against the crucial “freedom of worker movement” regulations, the EU Court ultimately sided on the state of sobriety in ruling that while “rules preventing Belgian clubs from fielding basketball players from other Member States where they have been transferred after a specified date constitute an obstacle to the freedom of movement for workers,” the reality was that “this obstacle may be justified on non-economic grounds which only concern sport as such. The setting of transfer deadlines may be intended to avoid distortion of the regularity of competitions.”

Lehtonen: Stirred the pot in his day

In other words, no guns-for-hire strictly for the purposes of, um, supplementing the roster before the playoffs would be allowed in EU states’ professional basketball leagues.

The Present: Sports organizers hopeful

Though some contend that recent statements from FIFA and the International Olympic Committee in praise of the Treaty of Lisbon reflect merely a greedy desire to return to “a simpler time when individual sports could run their own affairs the way they wanted without having to answer to the demands of labour laws or even, in some cases, basic human rights,” the bigger organizations rather imagine real opportunities for EU funds to support basketball and sport in general at its lowest levels.

Said IOC president Jacques Rogge in an official statement: “The impact of sport in the EU is huge, as is the influence of EU policies on sport. It really is time to move from a case-by-case approach to an environment where the specific characteristics of sport can be taken into account properly.”

Provisions for sport in the treaty include potential assistance for sporting clubs struggling financially, creation of “solidarity mechanisms” to compensate for some training costs, regulations on cross-border media rights, and an overall governing body (more on this below).

Certain proposals that were rejected back in 2008 and were not modified in the treaty’s present form included a ban on transfers of players younger than 18 years old (Can anyone else imagine an alternate-universe “Rubio Case”?), salary caps, and budget caps calling for clubs to depend fiscally only on “natural resources,” i.e. income derived from ticket, paraphernalia, and media sales.

Ultimately, this writer guesses that the newly-created Council of Sports Ministers will end up going down as the most important change to shape sport with the Treaty of Lisbon’s passage. Naturally, a few nations and professional sports organizations – notably Great Britain and Premiership football – opposed the creation of a “sports super regulator” and something of a compromise was reached giving a committee a supportive/promotional role. On this, European Olympic Committee president Patrick Hickey stated “We fully support this approach since the European Union should support and not regulate sport.”

The first-ever EU Council of Sport Ministers will be held in early 2010.

The Future: Too good to be true?

Can the Treaty of Lisbon really prove a boon to European basketball or will, as many hoops devotees on The Continent surely fear, any and all benefit to be gleaned from EU support simply be sucked up by the ubiquitous football? Though the Bosman Rule is surely here to stay (hey, free agency is the dominant mode of sports capitalism), Euroskeptics see the relevant articles as a hindrance to individual nations’ rights.

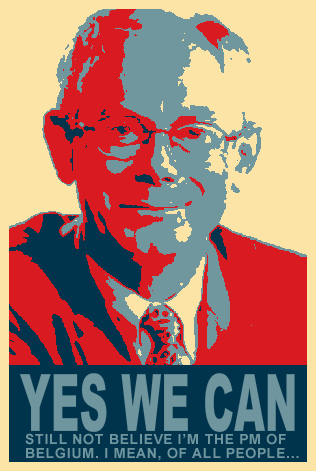

Van Rompuy: Obama for EU sport?

Belgian prime minister Herman Van Rompuy, now seen to be the vogue choice for the upcoming position of EU President, is unabashedly pro-Europe and even mentioned sport in drafting his party’s stance toward the Lisbon Treaty. “Apart from the euro, other national symbols need to be replaced by European symbols,” the manifesto states, including in a list of suggestions “one-time EU sports events.”

(Just imagine another off-season tournament featuring top EU clubs – too much is never enough!)

The joint statement from FIFA/IOC clearly supports the committee and the treaty:

“…The reference to sport in the Lisbon Treaty enables the set-up of a specific EU sports funding programme as well as a better mainstreaming of sport in existing programmes.

“In the coming months, the focus of the Olympic and Sports Movement, which took a clear and unified position on the autonomy and specificity of sport last year, will now be on the proper implementation of articles 6 and 165 [clauses dealing with culture and specifically sport].

“It is about protecting sport’s autonomy on the one side, and safeguarding the integrity of sporting competitions on the other side.”

We can only hope that the rosy vision of the FIFA/IOC comes to pass, because there are a lot of basketball programs that could use a little support, streamlining and/or straight-up bailouts right about now. Remember, Unionists, it’s good for culture!

Leave a Reply